WELCOME TO THE BIOSPHERE

― Ecologies of Food Production

↑ Enlai Hooi ― Courtesy of Schmidt Hammer Lassen

Enlai Hooi is the head of innovation at Schmidt Hammer Lassen. He is an architect and industrial designer specialising in integrating circular design, engineering, architecture and food systems.

Our food systems affect our health, communities, climate and global ecologies.This essay explores these systems through four key territories: the ocean, the forest, the countryside and the city, reflecting on the research behind The Hacktivist Guide to Food Security, and its relevance to architecture and urbanism.

Climate is Biology

It’s late spring. Copenhagen represents a pin-up city for the neatly packaged merger between a globalised talent market and the welfare society. Colonnades of trees are in bloom, and the skinny-dipping season has kicked off without a cloud in the sky. It takes a perverse mentality to harbour angst over the state of the environment at such moments. Yet, tractors and harvesters have encircled parliament house, food prices have jumped, and forest fires erupt in locations unaccustomed to heat waves.

Our biological allies, harboured in forests and oceans, are losing a territorial battle to our food systems. As our cities and societies developed beyond the biosphere’s capacity to self-regulate, our habit of conflating what we consider ‘normal’ with ‘reasonable’ has allowed daily life to displace the Holocene. Every five years we deliver the weight of the world’s forests in carbon to the atmosphere, subsumed imperceptibly into the fossil fuel engines that propel our economies (FAO, 2020; World in Data, 2023). Our seasons took 66 million years to stabilise, but that stability has collapsed within a lifetime (Lenton, 2008).

Aware that the world’s food supply is contingent on weather, and weather on biology, we might ask ourselves how food production has managed to depart from basic considerations of the earth’s ecosystems.Our food systems contribute a third of greenhouse emissions and the majority of planetary boundaries are exceeded due primarily to agriculture and fishing (Crippa 2021). One approach to reducing the impacts of food production and distribution could be to decrease the footprint of farming. The majority of planetary boundaries that are exceeded are primarily a result of agriculture and fishing practices. Another remedy to the negative impacts of farming and fishing could be to make our food systems regenerative. In the articles presented in this book, both approaches are explored. A range of strategies is needed in addressing the consequences of our destructive food systems as lasting solutions are contingent on context.

Oceans

The world’s oceans absorb around a quarter of the CO2 we produce and return half of the earth’s oxygen to the biosphere. In these unsupervised ex-terrestrial zones, phytoplankton photosynthesize carbon from nutrients and sunlight. Their role in the food chain is to convert energy into aquatic bodies that become matter on the ocean floor. The exoskeletons, abandoned shells of these tiny creatures that are constructed from calcium carbonate, dissolve in acidic water. This reaction permits more carbon to be absorbed as upwelling nutrients delivered to the surface of the sea trigger a surge of life.

Threats to the ocean’s ecosystems are unambiguous. Nutrient runoff from agriculture starves the water of oxygen. At the coasts, hypoxic dead-zones are created, laced with pesticides that mutate the bodies they encounter as they drift to the sea floor. A novel soup of synthetics have created environments toxic to those who feed from them. As fish populations decline and ocean temperatures rise, the once active churn of nutrients from the seafloor to the sunlit surface begins to stagnate (Katija, 2012). Sedentary aqueous strata slow the ocean currents, and the acidic top layer begins to expunge its carbon dioxide like a warm soda. Deprived of life, the sea only breathes out.

Forests

The story of the Amazon illustrates threats to the biosphere from forest clearing. The soil beneath the Amazon rainforest is nutrient poor; largely barren. A dormant desert, miraculously overgrown, drives the water cycle, feeding the rivers and tributaries that in return feed the metabolic chain of growth and decay. Over a desert, underneath the tropical sky. It appears odd that thousands of years of plant growth, biomass created by the reaction between sunlight, air and water has not built up a thick layer of humus: rich, black soil typical of potting mix formulated especially for tropical flora. Yet it remains that in many parts, the cover of leaf litter that sustains the cycle of nutrients providing the sustenance of the rainforest is only a few inches thick; it is a veneer of matter over sand and clay that preserves the necessary humidity and nutrients to support the abundance above. This fact is revealed each time a foot trail is tramped out through the undergrowth, or in the satellite imagery of a yellow arterial slicing its way through a bumpy blanket of green with its ubiquitous fronds, expressed as pixels of brightness—farmsteads and lumber clearings, annexed from the forest. These otherwise illegal claims on the land are supported by a string of governance loopholes that preserves the squatters’ rights – most often poor, hard-working farmers attempting to raise cattle or crops for the gluttonous open market, which is anything but open to them. One might presume that carved from the richness of the forest, yields would be promising and reliable, protected from erosion by the density of the surrounding flora and supported by the precipitation made regular by the transpiration of the canopy layer. But the richness evaporates quickly when not fed by the metabolism of leaf litter or studiously reinvested by the churn of natural fertilisers from animals and fungi living in the undergrowth.

So why, if gains are so small, do farmers fell, burn and clear land for grazing or soy production if they gain little for their efforts? One obscure, but simple dynamic at work, which results in this steady siege on the forest is explained in the following way. A law established to support the rights of the rural poor allows federal land to be converted to a title deed by means of occupation. If one can prove they have lived on the land for enough time, they have the right to claim it. For access to this right to claim the land, one requires literacy and legal acumen, which of course, is offered by agribusiness in return for the title itself. The deal includes a bonus that is just enough to make the continued march into the wilderness worthwhile for the impoverished. Because the smallholder farmers are in need of fertile farmland, the inexorable creep into the forests continues. Nothing substantial is gained, and everything else is lost. Once depleted, forest regrowth is painstakingly arduous. It appears that the Amazon rainforest is now a net emitter of carbon rather than a sink, a sign of a system in distress. This means on balance the forest is dying more than it is growing.

A number of small organisations are working to defend the rainforest by hindering logging, planting trees, and upholding native title. Certainly, working against this disposition is, in part, a social equity question. If we have the habit of excusing the ecological brutality of our own industries while working for a pay-cheque, it should be infinitely clear why farmers in Brazil do likewise. Unlike those in Western cities, a change in life direction is alien and risky. Livelihoods are made in generations, not in the salient years after a high-school prom. One organisation, Courageous Land, takes the local economies of farmers and ranchers into account. They offer an alternative, creating careers for farmers by growing regenerative crops that bolster the rainforest perimeter. The work pays better than logging and ranching, and it becomes easier over time, as balance is restored.

Countryside

The incremental industrialisation of our food has transformed the rural patchwork into a network of planar factories and logistics hubs. An ironically branded Green Revolution, made possible with exhumed sea-creatures and synthetic lightning, introduced plants to a world decoupled from the logic of ecology. Agriculture, no longer constrained by the necessity of biological nutrients to stimulate growth, has moved from traditional, biologically-based practices into industrialisation and the adoption of synthetic fertilisers and chemical inputs—its produce, offered to global traders, and waste-streams to local water bodies. Just as zoning regulations removed the threat of factories from intruding on the backyard vistas of the middle class, food production with the myth of the wholesome family farm still intact, has been swept from view. ‘Go big, or go home’, a euphemistic adage used by farmers to describe the pressure of mechanised expansion to make ends meet, masks its corollary: that humans are an expense that agriculture can no longer afford.

A catalyst for this territorial metamorphosis is revealed when we treat food as a commodity—a basic good that is interchangeable and essentially uniform across producers—and it hinges on two fundamental principles in trade: homogeneity and waste. If everything produced was consumed, the market would collapse since profitability relies on the potential to source the same items at a lower cost elsewhere.

Commodity-economics has a habit of exploitation, honouring the lowest bid irrespective of the casualties. Farmers enter the debt spiral, caught in a pincer move between agrochemical companies and a retail-door policy that excludes the ugly and the unusual. Children adorn the doorsteps of rural villages with pesticide-induced deformities. Penicillin-resistant bacteria find new hosts in humans in the confines of Danish piggeries. Locked into the ‘free’ market, infamous for its crashes, our food system fails to account for systematic risks, and people are part of the collateral damage.

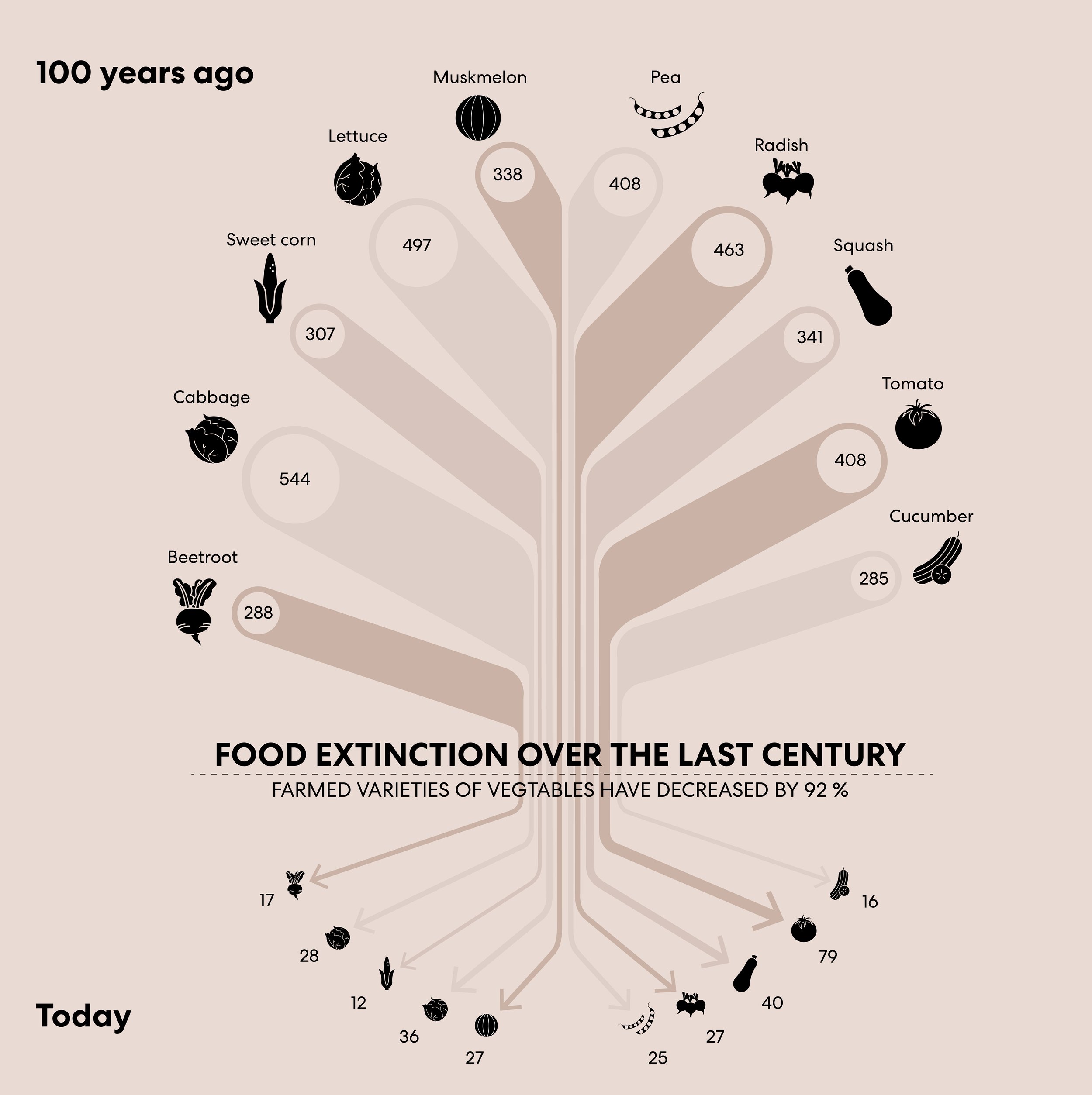

As farmers conform to these retail trade standards, the nutritional content, taste, smell, and texture—the signs of life—slink away from land and plate as they elude cursory comparisons in trading warehouses. Instead the metrics of colour, size, shape and weight, supplant nutrition and sensory stimulation, replaced with empty calories and a spritz of glyphosate. In the alignment problem between the food industry’s ‘quality standards’ and our health, poison is presented as sustenance.

Growers exploit the technologies, the land, and themselves to compete with the global labour baseline. In a monopolised paradigm of supply and demand, food retail is no longer the marketplace but the market itself. The consumer remains, simply to consume. With the loss of biodiversity in our diet, our bodies turn on us. The human microbiome, a complex world of creatures expecting threats from the biosphere, starts to rebel when underchallenged by nature and outgunned by chemicals.

City

We might see the city in two ways. The first is the city as an actor in the biosphere—an entity in itself—an organism of production and consumption that represents the urban condition. The other is the city as a collection of people, their relationships and social contracts, formed through physical infrastructures, economies and shared identities. These frameworks are not divorced from one another. Churchill’s quip, ‘We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us’, acknowledges that we are enmeshed with the environments in which we reside, and that our environments themselves are malleable, continuously retrofitted and recomposed.

As entities, urban areas perform poorly in ecological terms. They occupy a fifth of a percent of the earth’s land mass, consume nearly 80 percent of its food, and create nearly all of what we consider to be waste. Through agriculture, construction, mining, fishing and other forms of resource extraction, they dominate an oversized backstage of territories on which they depend. However, the notion of urban vs rural sets up an unhelpful dichotomy, anchored in the precept of the post-industrial city where zoning policies draw lines around what can and cannot be done in designated areas. In reality, the structure of urban environments is anything but homogenous, and since the countryside itself has become industrialised, arguments for segregation of urban and rural have become tenuous at best. Whether sufficiency can or cannot be achieved within defined geographical borders is immaterial to the aim of reinvesting urban spaces with the capability and output of productive ecologies.

If we consider the city, not as an object, but as a collective of people that might benefit from a closer relationship to sources of sustenance, the justifications for bringing food production closer to people’s daily lives become even more compelling. As an extension of this consideration, our food environment—our agency over the possibilities available to us—are mediated by urban infrastructures. These considerations prompt us to rethink the role of architects and urbanists, and the challenges they represent to conventional practices. Given the profession’s structure, and how projects evolve from the brief to the delivery, greater interaction between designers and the communities they serve is required for food systems to play a positive role in urban design and architecture. City design inevitably influences social transformation, and we reshape cities through social value propositions. The intricate relationship between communities and food—involving access to healthy ingredients, attitudes, cultural identities, and shared responsibilities—calls for a nuanced approach, requiring collaboration of designers, consultants and local authorities working with communities, to deliver projects.

There appears to be a collective reticence to exploring food production in urban areas. In a modern perspective, success of civilisation is marked by freedom from subsistence. Yet a fundamental desire to reconnect with both nature and productive labour in cities is apparent. As zoning policies are amended to encourage artisans and light industry to return to civic centres, our cities are granted food-growing spaces, and the pleasure of production is back on the agenda, along with the diversity that arises from expression of desires between grower and consumer.

Rather than needing to disengage with civic life to have a meaningful relationship with food and nature, there are spaces in cities around the world that redefine civic life. Within the city of Sao Paulo, thirty-one organic market gardens covering around 230,000m2 weave their way into the urban fabric, occupying remnant infrastructural spaces of the poorest neighbourhoods. Cidades Sem Fome (Cities Without Hunger) pay at least triple the minimum wage and provide food security to over 500 workers. Its poorest citizens have begun to eat well, learn to read and write, and take holidays. At Phood Farm in Eindhoven, long-term unemployed and ex-prisoners produce food in the city centre as a social rehabilitation therapy, where people are able to see the practical result of their work and gain respect and empathy for nature and their colleagues. In New York, Brooklyn Grange conducts an educational curriculum for the host of cultures that constitute their neighbourhoods that reestablishes the ingredients, practices and communities of diasporic migrants.

A motivation of desire results from an apprehension of potential alternatives to the way food intersects with our lives. It stems from a dissatisfaction with food systems more concerned with wealth generation than with nurturing life, coupled with the education and agency that enables us to imagine different ways of living. Given that over half the world’s population now resides in urban areas, we might see cities as the testing ground for that change.

Welcome to the Biosphere

This is where we live. A multitude of approaches is required to establish food resilience and security if we consider the precarity of the Holocene and our food systems. What is less apparent are the opportunities inherent in these transformations to enhance our daily lives. The Hacktivist Guide to Food Security is conceived as a tool that can stimulate new conversations and insights of how food systems might be recomposed to transform cities, landscapes and oceans for our mutual benefit.